Review: Not About Heroes, Wilton’s Music Hall

by Adrian Gillan for Bent Gay Shopping & Magazine

A hundred years on since WW1 ended, Bent’s Adrian Gillan hails the timely revival of a play exploring war, pity and poetry; and the friendship between two Great War gay greats!

First performed in 1982, at the Edinburgh Festival, Stephen MacDonald’s two-hander Not About Heroes examines the real-life relationship between WW1 poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon.

Sassoon, who survived the war, relates the story via extracts from actual diaries and letters, and via a series of flashbacks, mostly to scenes set at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, where he and Owen first met, as fellow patients, in 1917.

The play’s title is a quote from Owen’s famous preface to his collected poems that were only published posthumously, he himself being killed in action just a week before the end of hostilities: “This book is not about heroes… The subject of it is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

The original Edinburgh production toured and came to the King’s Head Theatre in London, and was adapted for Yorkshire TV and BBC Radio 4. Subsequent numerous stagings have included the Royal National Theatre; the Glasgow Citizen’s Theatre; a tour that took in Craiglockhart Hospital itself; and another tour that took in the Imperial War Museum North, Cabinet War Rooms and Trafalgar Studios in London. There have also been several productions overseas, notably in North America and Australia.

Presented by Flying Bridge Theatre Company and Seabright Productions, this latest rendition has already won a Best Actor accolade at the Wales Theatre Awards for Daniel Llewelyn Williams, who reprises his role here as Sassoon, alongside Owain Gwynn as Owen.

These two actors are quite remarkable, Llewelyn Williams’ outwardly coldly suave yet inwardly sensitive and traumatised Sassoon contrasting effectively with Gwynn’s outwardly shell-shocked gentle yet inwardly steely and ultimately transcendent Owen. The shifting dynamic of their mutual respect and the moral ambiguity of their combative motivations – including crude revenge, homoerotic camaraderie, disproof of self-doubt and a sheer existentialist drive to live life on, even over, the edge – add an all-too-human complexity and depth to the drama, which bubbles up organically, from time-to-time, into recitals of the now famous war poetry; and which is punctuated, throughout, with humour, both light and dark.

Tim Baker’s deft direction delivers a suitably subtle treatment of any homosexual subtext and holds sentimentality at bay as the increasingly looming doom unfolds; served by Oliver Harman’s simple touring set, plus restrained lights and sound, by Kevin Heyes and Dyfan Jones respectively.

This London run has concluded an acclaimed two-year tour, commemorating the centenary of the ending of The Great War, the very last show happening on 11 Nov, Armistice Day itself.

BOX OUT: GAY GREAT WAR POETS

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967)

Sent to France in 1915, Sassoon was nicknamed ‘Mad Jack’ for near-suicidal bravery, being decorated twice, including a Military Cross. Wounded in 1917, he came home – increasingly, and publicly, disillusioned with the war. Treated at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, he there met, and influenced, Wilfred Owen.

Wounded again on the Western Front, Sassoon spent the rest of the war in England, publishing poems. His darkly sarcastic Memorial Tablet includes the line: “I died in hell (They called it Passchendaele).”

Post-war, Sassoon did much public speaking, whilst penning novels, including Memoirs of a Fox-hunting Man (1928). He had a number of affairs with men but surprised friends by marrying in 1933, and siring a son, although this marriage broke up after WW2. He died in 1967.

Wilfred Owen (1893-1918)

Owen was sent to the Western Front in 1917. Shell-shocked, he was treated at Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh where he met Siegfried Sassoon.

Returning to France in August 1918, Owen was himself awarded the Military Cross for bravery in October, and was killed on 4 November while trying to lead his men across a canal. His parents received news of his death on 11 November: Armistice Day.

Published in 1920, edited by Sassoon, Owen’s sole poetry volume contains, arguably, the finest war poems ever written in English – not least Dulce et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth.

Writer Robert Graves, and other personal acquaintances, have claimed that Owen was homosexual, and homoeroticism does seem a central element of much of his poetry. Through Sassoon, Owen met a sophisticated homosexual literary circle, notably Scottish writer C. K. Scott-Moncrieff. Intriguingly, Owen asked his mother to burn a sack of personal papers after his death; and his brother subsequently cut certain passages from Wilfred’s letters and diaries.

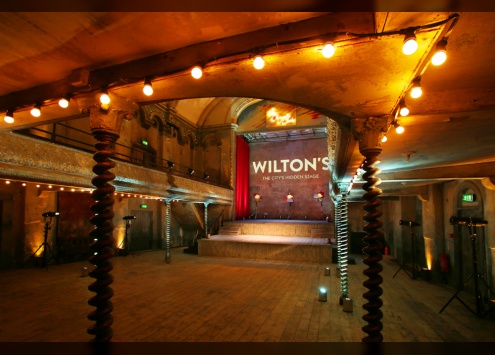

WILTON’S MUSIC HALL

Grade II*-listed Wilton’s Music Hall is arguably Britain’s (hence the world’s) oldest surviving “music hall”, now saved from the bulldozers, having undergone “conservative repair” to preserve many of its original features, and is now run as a multi-arts performance space in Graces Alley, off Cable Street near Tower Hill in London – offering an aptly contemporary take on its original variety purpose.

Under various phases of enlargements, the hall was active as one of London’s premiere early-to-mid-Victorian music halls, for about three decades, commencing 1839 – attached to a tad older mid-18th Century terrace of three houses, and a pub that acted as both entrance and refreshment house. Many legendary acts of early popular entertainment performed here, from George Ware who wrote ‘The Boy I love is up in the Gallery’ to George Leybourne (Champagne Charlie).

It was gutted by fire in 1877, rebuilt and then used as a Methodist Mission, to help alleviate surrounding poverty, for seventy years until after WW2. Then, following a brief time as a rag storage warehouse, it was earmarked for demolition until a campaign, fronted by the likes of Sir John Betjeman, Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan, got it listed, in 1971, thus saving it!

Wilton’s reopened as a theatre and concert hall in 1997 and has been a producing and hosting space since 2004, at which time it was still derelict and in debt.

Over the next decade, thanks to donations and grants, the building has been restored, including the reinstatement of The Mahogany Bar and wider front-of-house. A new Learning and Participation Studio has also been created. The project was completed in September 2015 leaving the building structurally secure – probably for the first time since the renovations of music hall days.

The theatre is an unrestored example of a ‘giant pub hall’. In the theatre, a single gallery – on three sides and supported by ‘barley sugar’ cast iron pillars – rises above a large rectangular hall and a high stage with a proscenium arch. The hall would have had space for supper tables, a benched area, and promenades around the outside for standing customers. Wilton’s was modelled on many other successful London halls of the time. It now remains the only surviving example.

The hall and facilities are owned and managed by the Wilton’s Music Hall Trust as an arts and heritage venue. It produces and hosts imaginative, distinctive work that has roots in the early music hall tradition, but reinterpreted for an audience of today, which means presenting a diverse and distinct programme including opera, puppetry, classical music, cabaret, dance, and magic. Situated at the heart of the historic East End, it is a living theatre, concert hall, public bar and heritage site.

Its two bars are open Monday to Saturday, 5pm to 11pm, and also open early for matinee performances where applicable. The Mahogany Bar is a much-loved destination in its own right, serving a carefully selected range of beers, wines and spirits, locally sourced where possible. The Cocktail Bar has been transformed into a gin palace, serving an exclusive menu of specialty gins, plus a range of wines, bottle beers and soft drinks. Caterers, The Gatherers, serve a seasonal menu, including their famous stone-baked pizzas, on show days only from 5pm to 9pm. Food can be eaten in the Mahogany Bar or taken up to the Cocktail Bar. A separate lighter lunch menu – including focaccia sandwiches and a range of delicious salads – is available from 1pm on days with matinee performances.

Other forthcoming productions at Wilton’s Music Hall include: Ballet Boyz: Young Men (13-17 Nov 2018); Dietrich: Natural Duty (19-24 Nov 2018); Xmas show, The Box of Delights (30 Nov 2018 – 5 Jan 2019); The Pirates of Penzance (20 Feb – 16 March 2019); and Margaret Thatcher Queen of Soho (26-30 March 2019), to coincide with the UK leaving the EU.