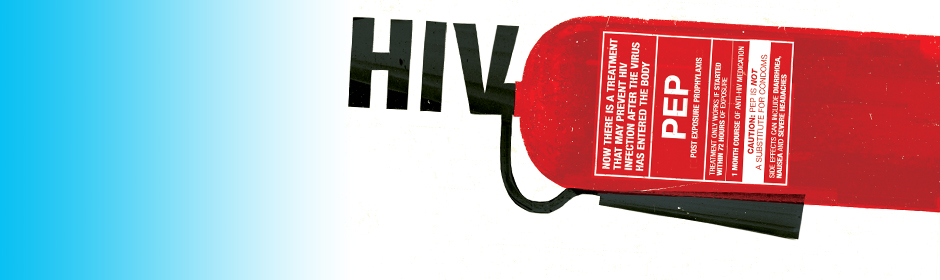

BEYONCE ENCOUNTERS . . . PEP (Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

‘Do you have any water?’ Pete asks in the A&E department. It’s a Sunday evening, and most of the people still queuing up here are casualties from Saturday-night revelries. We’re all being punished for our weekend excesses, it seems. There are people with bust lips and broken limbs. People in wheelchairs and on crutches. People still drunk from the night before. We just sit there like sinners waiting for confession.

I reach into my man bag and grab what the label claims is a bottle of Harrogate Spring Water. I twist off the top and get a full-on whiff of gin.

‘Erm, actually, I forgot I put gin and lemonade in this.’

‘Maybe that’s a sign,’ Pete says, and knocks back a potent mouthful.

Four hours in and I’m beginning to agree with him.

‘How long did it take when you came for PEP?’ he asks.

‘Me? Well I went to the clap clinic. They were quicker. A lot quicker. But the whole thing still took a few hours. They were really nice there though. I think they’re a bit too busy here for nice.’

‘Shoulda gone there. We’d have been seen and gone by now.’

‘Clap clinics aren’t open on a Sunday, Pete. They intentionally only open them during working hours, so that regular people can’t attend. They want the regular people to humiliate themselves by going to A&E or a GP’s surgery. They save the clap clinics for students and prostitutes. The rest of us—we have to be punished. We should know better.’

‘Next time I’ll remember to only bareback on a school night, then.’

‘Next time you’ll remember to wear a condom.’

‘Yeah, that too.’

He takes another swig from our surreptitious booze and then passes it to me. I take a gulp, but it’s too dry to do anything for my thirst.

‘Peter Clayton!’ calls the nurse from the other end of the waiting room.

‘You’re up,’ I say.

The nurse leads us into a small room and sits Peter down. I take a seat beside him.

‘So what can I do for you today?’ She’s casual like a newsagent. Like we’re buying a paper or cigarettes. But she smiles, at least.

Then Peter tells her the story. It’s a typical one I’ve heard many times before: boy goes out, boy gets drunk, boy meets boy, boy takes boy home, boy wakes up in the morning not quite sure what’s happened and with a head full of regrets. Except I think there was something in there about blood on the sheets.

‘Okay, well let me take your bloods first,’ she says. And I think about the use of the word ‘bloods’. Because we have more than one kind of blood, apparently: good blood and bad blood. She’s checking for the bad blood alright. She’s checking for signs of sin.

‘Now I’ll need you to fill this up,’ she hands him a beaker, ‘and then go back to the waiting room. You’ll need to speak to a consultant. It’s not like the morning after pill, you know.’

‘Four hours for two minutes with a smiling nurse. I guess it’s not as bad as the build-up suggests,’ Pete says.

The consultant is also straight to the point. ‘Normally we only give PEP in exceptional circumstances.’ He paused. ‘Do you know the person you slept with?’

‘I know of him. He works near me,’ says Pete.

‘Have you asked him if he’s HIV positive?’

‘No, I haven’t. I don’t have his number and—’

‘Okay. Well we’d normally ask you to ask him before we give you PEP. It’s a very costly treatment and it’s not without side-effects.’

I interrupt. ‘I only got diarrhoea.’

‘That may be, but everyone reacts differently. Some people lose their hair. It can cause damage to the kidneys. Some people suffer nausea and loss of appetite.’

‘Sure, but if he gets HIV, he might get some of those symptoms anyway. Surely it’s better to go through it for a month than to have to take the same tablets for the rest of his life?’

‘You said you were top, Peter, right?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then your chance of contracting the virus is very low without other factors.’

‘Tell him about the blood!’ I say. Yes, doctors understand blood. Bad blood.

‘What blood?’

‘There was bleeding, I think. I saw some blood on the sheets.’

‘I see.’ The doctor looks at his computer monitor for a moment. It’s just Pete’s name and address, so I’m not sure why. Maybe he’s trying to gather his thoughts.

‘Does that change anything?’

‘You should have mentioned that earlier.’ His face softens a bit. Yes, doctors understand blood.

‘I’m just—it’s all been so quick.’ I can see him breathing quickly.

‘I’m going to prescribe it this once. But I really think there’s little chance of you catching it.’

‘Better to be safe than sorry, though,’ I say.

The doctor looks at me. ‘And you should both know better.’

I leave A&E exhausted. We’ve been waiting for hours. The whole thing’s taken six hours, including the time waiting at the pharmacy. Pete is clearly upset.

‘Have you seen the size of these tablets?’ he asks.

‘You’ve put bigger things in your mouth.’

‘And that’s what’s got me into this mess.’ He looks at me, all the seriousness he can muster in his eyes. ‘I’m scared.’

‘Don’t be scared, just don’t be stupid again.’

‘I didn’t plan it.’

‘Most of us don’t.’

‘I didn’t want this.’

‘I know.’

‘What should I do?’

‘Have a swig of this. It’ll help you swallow.’

He looks ashamed. I understand that feeling. That’s the worst part about it. It’s the stigma. Because if we’re here to get PEP, then we’ve fucked up. There’s no other way to rectify it. It’s not like we’ll just get pregnant and have a baby. It’s something we’ll be judged for. Pregnancy’s a beautiful thing, but HIV . . . ?

I’m not scared of the illness so much. I’m scared of what other people will think and the way they’d treat me if I caught it. I’m scared of telling people. I know that all the education in the world won’t stop most people seeing it as a gay disease, and that many people will think it’s our own fault. It’s not like cancer, is it? Most people donate to Macmillan. How many people, outside our own community, donate to HIV charities? It’s just not the same.

And when I look over at Pete’s eyes, I understand that he’s scared of all these things too. And I wish we weren’t. I wish people would understand this is an illness, not some mystical judgement placed upon us for our misdeeds.

‘Actually, pass the bottle back. I think I need a swig of this first.’

www.pep.chapsonline.org.uk/pep_basics.htm

www.pep.chapsonline.org.uk/pep_basics.htm