Review: The Night of the Iguana, Noël Coward Theatre, London

by Adrian Gillan for www.bent.com

Chekov in the jungle! Bent’s Adrian Gillan hails a revival of gay great Tennessee Williams’ The Night of the Iguana, as restless souls yearn for release, at the Noël Coward Theatre in London!

Take a disgraced priest with a taste for alcohol, teenage girls and regular self-consciously histrionic nervous breakdowns; a man-eating recently-widowed hotel owner who screws her young employees and has the hots for said priest; and a resilient but sexually unfulfilled itinerant female spinster artist who paints for her supper and makes said hotel owner wildly jealous by also seemingly having the hots for said priest – and the result is a battle of wills between tortured spirits, and twixt carnal and deeper loves.

With the poetic symbolism of his beloved Chekov, Tennessee Williams metaphorically sets this psycho-collision in a remote lofty rundown hotel, tucked away in the Mexican jungle, surrounded by strange noises and mountain mists – where storms build and burst, and where a captive wild iguana is ultimately set free, as characters stumble towards a typically uncertain Chekhovian future.

Based on a real-life low-ebb encounter in 1940, when The Night of the Iguana is set, Williams’ original short story morphed, over the course of many years, into initially a one-, then a two-, then finally a three-act play, that received its Broadway premiere in 1961, before being adapted into a 1964 film starring Richard Burton. Rarely performed in London, most notably at the National Theatre in 1992 and in the West End in 2005, this latest British revival features some fine performances and a stunning setting.

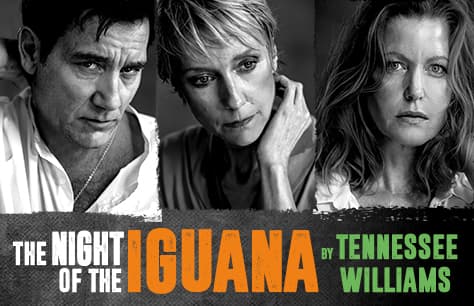

In his first West End appearance in almost two decades, Clive Owen truly gives his all as the evasive, vacillating, complex Reverend Shannon, battling his taboo sexual and addictive demons – just as Tennessee Williams himself had to, in his own gay way. Owen invests the character with enough humour, irascible charm and sheer lust-for-life for us to almost forgive its inescapable unlikability – the guilt-ridden violent appetite for teenage girls, the bullying tendencies and almost total self-absorption.

Lia Williams is wonderfully resolute-yet-remote as nomadic artist Hannah, travelling with her charmer nonagenarian grandfather, Nonno – veteran Julian Glover, movingly struggling to finish his last poem, dementia fast descending – the pair of them precariously hustling out an existence, selling paintings and poems, like a pair of exotic, Bohemian travelling salespersons: that ubiquitous hallmark Williams motif!

Anna Gunn plays promiscuous hotelier widower Maxine in a low-key, naturalistic vein: perhaps we need something a tad more deeply smouldering, à la tragic femme-fatale, as sultry as the leafy surrounds.

In the smaller roles, Emma Canning milks Lolita-like teen Charlotte for all she’s worth, chaperoned by suitably frumpy, feisty, though not-exactly-“butch”, Finty Williams as Judith. Faz Singhateh is excellent as Shannon’s friend-turned-enemy bus driver, Hank; and Ian Drysdale spot-on as his replacement tour guide, Jake. Added layers of well-nigh pantomimic comedy are provided by Maxine’s two speechless sexy young impudent male hotel staff; and by the brash model Nazi family hotel guests who sporadically cross-stage, jubilantly celebrating ongoing German victories in Europe, notably the Blitz here in London!

This may not be amongst Williams’ very greatest plays, and the three hours do start to feel their length, but director James Macdonald is very successful in evoking the work’s humid, heightened atmosphere. This is in no small measure thanks to his exquisite creative trio of Rae Smith (design), Neil Austin (lights) and Max Pappenheim (sound) – surely at least a few nominations beckon – who conjure up a vertiginous set, cliffs and palms looming above, imagined echoey chasms stretching below; and the climactic thunderous storm pre-interval shall long linger in the memory. Worth the ticket, alone!

Tennessee Williams (1911 – 1983)

Generally considered to have been one of the three giants of 20th Century American drama, alongside fellow playwrights Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams wrote perhaps his three best-known plays within a decade, from mid-1940s to mid-1950s – The Glass Menagerie (1944), A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955). Many of his works were made into films.

He had a violent, drunken travelling salesman for a father and a difficult relationship with his mother; but he adored and financially supported his institutionalised schizophrenic and lobotomised sister. He had a series of gay affairs, oft with significantly younger men, many drink- or drug-dependent – as Williams himself increasingly became, suffering from anxiety and depression. Some were attracted by his fame and burgeoning wealth. Occasional actor Frank Merlo was the enduring, 14-year, romantic relationship of his life, the pair living in both New York and Key West during his most artistically productive years.

Williams choked to death on a plastic bottle cap in his Manhattan hotel suit in 1983 and was buried in St. Louis, Missouri, despite the express request, stated in his will, that his body be disposed of at sea.

The Night of the Iguana runs at the Noël Coward Theatre in London, until 28 Sept 2019.

– ends –