Going nuts over Matthew Bourne By Lyndsey Winship

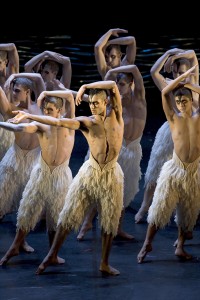

There’s no-one in the dance world quite like Matthew Bourne. Not many people can say they’ve invented a new genre of dance, but Bourne could make that claim. The choreographer has made his name reinventing the classics with a twist, like Swan Lake, where he famously made all the swans male, or Cinderella, where he turned a well-worn fairy tale into a cinematic wartime romance.

His work lies somewhere between dance, theatre and silent film – you could call it movement-theatre, or wordless storytelling. But whatever you call it, it’s hugely popular, with endless sell-out shows, worldwide tours and celebrities such as Johnny Depp, Jack Nicholson and Stephen Fry are queuing up to gush about the man’s talents. As well as currently working on a new projects, Bourne is touring his souped-up version of ballet classic Nutcracker!, a kitsch and colourful take on the traditional story that’s as fun and fresh now as it was when it was originally made 20 years ago.

It’s your company’s 25th anniversary. Did you ever anticipate getting this far? Was there a grand plan?

No, there was no big grand plan. In the early days it was just from performance to performance. It was all unpaid and we all had part time jobs. We got together as a company just for the chance to choreograph and to perform. At that point we would never have dreamt it would have led here.

You came to formal dance training quite late. What made you decide that dance was the medium you wanted to work in?

I think I was after something to express myself with and knew I wanted to entertain. From a very early age I was always putting on a show in some form or other. I became a big movie fan and was taken to the theatre by my parents. I thought I wanted to act, I thought that was my destiny, and then I tried it and I didn’t like using my voice! I felt really uncomfortable with my voice at that age, 14-15, and so it sort of gradually moved towards dance being the thing. I think the things that were always there were storytelling and wanting to entertain people.

When you came out of college in the late-80s, the contemporary dance scene was very alternative and experimental, with people like Michael Clark and Lea Anderson. Storytelling and entertainment were pretty unfashionable, weren’t they?

They were, very unfashionable. Obviously when you’re a student you try and please your teachers and I was trying to do what I thought was the right thing. It took until I got to the third year till I thought I should be doing what’s right for me, something that’s from the heart, rather than trying to second guess the trends.

Nutcracker was the show that set you on the path to success, your first re-writing of a classic. How did it come about?

Opera North, and their then Director Nicolas Payne, came to us in 1992 and said they were recreating the bill on which Nutcracker was premiered in 1892 with the opera Iolanta, for its centenary. There were a lot of classical versions around and they thought they’d ask someone who could do something a bit different with it. They’d seen one of our small pieces, with a cast of six people. It was a big leap of faith on their part, to pick me to do it. I can’t imagine anyone doing that now.

That famous Tchaikovsky music was the first big classical score you’d tackled. Did you already know the music?

I’d seen the ballet a few times, and I knew some of the music from Fantasia, which I’d seen when I was a kid. I wasn’t brought up with classical music in the house, it was all musicals, but I loved it. To me, Tchaikovsky’s music is the best musical ever written without words. It’s one melody after another. You do come out humming the tunes.

Tchaikovsky wrote the music for Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake as well. What made him so good at ballet music?

He was obviously brilliant at melody and orchestration, but I think it’s more than that. I think it was a lot to do with the closeness of the collaboration [between composer and choreographer] when they were made. It was concise; he couldn’t waffle on, whereas when you’re writing a symphony… maybe ‘waffling on’ is the wrong term!

He had to think of a different melody for each dance. You have these brief numbers where you get one idea and another idea and another. Especially in this day and age where attention span is brief, I think it suits the modern age, in a way.

Do you start with the music when you’re making a piece? What comes into your head – images, movements, emotions?

All those things. Sometimes when I’m on a train and I’ve got nothing to do but listen, I visualise a whole series of moves and dances, and I think, oh god, it’s going so well in my head, I wish I could remember all this! Sometimes I’m really just trying to find a way of telling a story and it’s not about movement. It’s the rhythm of the evening that’s very important to me, the arc of the story.

How much has Nutcracker changed from the first performance?

A lot! It had a big overhaul 10 years ago and since then it’s had little bits and pieces. There’s a moment when the character Fritz gets snowballs thrown at him to get him off the stage, that only came in a couple of weeks ago. I love reviving and redoing pieces because every day there’s something more to say. It’s an ongoing, movable feast. That’s why I love live theatre as opposed to film. You can keep growing.

Do you change things accordong to audience reaction?

Yes, very much. We talk about that a lot, at each venue we go to: What did they get last night, what didn’t they get?

Not all choreographers think like that…

I think I’ve learned all that from directors I’ve worked with in musical theatre. All the things I’ve heard Trevor Nunn or Richard Eyre say. I learned that for those directors, pace is the most important thing. Don’t let the audience drop – that happens in dance massively, all the time: someone comes on, walks to a space, miserable face, starts to move, stops. It doesn’t grab me. I want more than that. You need to take the people and lift them, take them with you. I find audience psychology fascinating. I’m a person who sits in audiences a lot, to experience their experience.

Are you sometimes surprised at the audience’s reaction?

Completely, always. There are always things you think are really good that no-one gets, or no-one seems to notice. And then sometimes there’s a reaction to something, and you go, what are they looking at?

Photos: Simon Annand/Bill Cooper