Why cottaging still matters.

In 2008 Jeff Akers, a retired accountant, went into a public toilet in the small town of Walton in Surrey where he was stabbed to death in a homophobic attack. Akers was openly gay. He had a partner of some two decades. And although we’ll never know for sure what he was doing that day, the assumption has been that he was cottaging.

In 2008 Jeff Akers, a retired accountant, went into a public toilet in the small town of Walton in Surrey where he was stabbed to death in a homophobic attack. Akers was openly gay. He had a partner of some two decades. And although we’ll never know for sure what he was doing that day, the assumption has been that he was cottaging.

But why?

We live in an age of the ‘dating’ app and equal marriage. Homosexuality is no longer something to be hidden away. Attitudes have changed. Meanwhile cruising has moved to the online world. Go into any gay bar, log into your Grindr account and you’ll find plenty of guys cruising virtually just metres away. There has been a cultural shift against the cottage in mainstream gay society as representing something from the ‘bad old days’ but also an activity which goes against our somewhat bourgeois, adopted values.

It is undeniable that cottaging has declined but the importance of the cottage endures.

When my friend and filmmaker, Adam, approached me with the idea of making a film about cottaging, I immediately said ‘yes’. As a young man I used to cottage and had told him plenty of stories. We’d interview a few academics, maybe Peter Tatchell; we’d get someone to stand in a carrier bag in a toilet cubicle as they used to. It would be irreverent, cheeky and bold. Yet as I explored the subject I thought that there was something more to this than just the death of a relic from a less tolerant age.

Cottaging has been around since the erection of toilet blocks. In fact the term ‘cottaging’ comes from the nature of those 19th Century public toilets, which were small buildings tucked away in parks and lined with hedges and small gardens in a time when to admit the need to defecate was unseemly. Without a gay scene and when homosexual sex (even between consenting adults) was illegal, toilets were one of the few places where men could meet men for sex.

Cottaging has been around since the erection of toilet blocks. In fact the term ‘cottaging’ comes from the nature of those 19th Century public toilets, which were small buildings tucked away in parks and lined with hedges and small gardens in a time when to admit the need to defecate was unseemly. Without a gay scene and when homosexual sex (even between consenting adults) was illegal, toilets were one of the few places where men could meet men for sex.

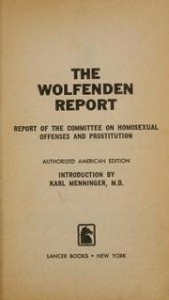

In 1952 the actor John Gielgud was arrested for cottaging. He was near the peak of his fame but fell victim to a sting operation which led to his arrest. He was recognised by a reporter when he appeared in front of the magistrate and, despite giving a false name, found himself exposed in The Evening Standard. Gielgud’s arrest was “the biggest gay scandal since Oscar Wilde” (imprisoned in 1895), but the condemnation was not universal. Although large portions of the population were shocked and revolted, there was a measure of sympathy for him as well. His arrest began the process which lead to 1957 The Wolfenden Report, and the eventual decriminalisation of homosexuality ten years later.

In 1952 the actor John Gielgud was arrested for cottaging. He was near the peak of his fame but fell victim to a sting operation which led to his arrest. He was recognised by a reporter when he appeared in front of the magistrate and, despite giving a false name, found himself exposed in The Evening Standard. Gielgud’s arrest was “the biggest gay scandal since Oscar Wilde” (imprisoned in 1895), but the condemnation was not universal. Although large portions of the population were shocked and revolted, there was a measure of sympathy for him as well. His arrest began the process which lead to 1957 The Wolfenden Report, and the eventual decriminalisation of homosexuality ten years later.

Gielgud was not the only cottager who has had an impact on our consciousness. Joe Meek, the music producer, committed suicide when blackmailed over his cottaging; the Labour MP Tom Driberg was so famous for his cottaging that the police used to collect him from public toilets for important votes in the House of Commons; perhaps most famously Joe Orton catalogued his cottaging and cruising in his iconic diaries. They are all part of something called ‘gay history’.

When researching the documentary I was struck by the number of gay and bisexual men who wrote to say that they used to cottage and missed cottaging. They secretly yearned for the days when they cruised public lavatories on the way home from work or after an evening out. Cottaging was not only an act of necessity. It became a venue of choice for some. I was also struck by how we recreate the cottage in porn and in sex clubs. The toilet is a place where men are exposed. Like the sports locker room or shower it is an undeniably masculine environment. The eroticism of risk plays a part, but so does the raw sexuality which cottaging represents: this is not sex for any purpose except to have sex.

When researching the documentary I was struck by the number of gay and bisexual men who wrote to say that they used to cottage and missed cottaging. They secretly yearned for the days when they cruised public lavatories on the way home from work or after an evening out. Cottaging was not only an act of necessity. It became a venue of choice for some. I was also struck by how we recreate the cottage in porn and in sex clubs. The toilet is a place where men are exposed. Like the sports locker room or shower it is an undeniably masculine environment. The eroticism of risk plays a part, but so does the raw sexuality which cottaging represents: this is not sex for any purpose except to have sex.

For some people it is still a reality. Sexuality is difficult. The recent gay marriage debate may have exposed the feeble arguments of opponents and left religious organisations fumbling for relevance but it is not the complete picture: outside of the UK’s big metropolises homophobia still exists. It also exists inside them as well. ‘Gay’ is still slang for ‘lame’ or ‘crap’. In a world where heterosexuality is the presumed norm we not only have to deal with obstinate prejudices and expectations, but also our own of what our lives will be like. For people still in the closet cottaging is a way to have sex. Of course, they could perhaps more easily find sex using Gaydar or Grindr but people are not always rational beings, are they?

What I find surprising is that the reluctance to address the positive aspects of cottaging. Cottaging has become rather like that disreputable aunt who no longer gets an invitation for Christmas. People are prepared to talk about police entrapment and homophobia but not that this was just gay men doing what gay men should do: have sex. To adapt Aristotle, gay men are sexual animals. It is (pun alert) an inconvenient truth. The gay community bought into the slightly homophobic hysteria which said that cottaging was irresponsible. Straight people cruise – think dogging – but do not have to tolerate the argument that other people or kids might see. So let me just say that in all the years I cottaged, no member of the public ever saw me have sex. No kids. No animals. Not even my disreputable aunt. There is an implicit purchase of the heterosexual orthodoxy of the “good homosexual” and the “bad homosexual”: to be treated equally we have to behave.

What I find surprising is that the reluctance to address the positive aspects of cottaging. Cottaging has become rather like that disreputable aunt who no longer gets an invitation for Christmas. People are prepared to talk about police entrapment and homophobia but not that this was just gay men doing what gay men should do: have sex. To adapt Aristotle, gay men are sexual animals. It is (pun alert) an inconvenient truth. The gay community bought into the slightly homophobic hysteria which said that cottaging was irresponsible. Straight people cruise – think dogging – but do not have to tolerate the argument that other people or kids might see. So let me just say that in all the years I cottaged, no member of the public ever saw me have sex. No kids. No animals. Not even my disreputable aunt. There is an implicit purchase of the heterosexual orthodoxy of the “good homosexual” and the “bad homosexual”: to be treated equally we have to behave.

I am not advocating a right to cottage, or saying that cottaging should exist as part of gay culture. I am saying that it did exist as part of gay culture and it does exist on the fringes today. What I am saying is that to ignore it isn’t healthy.

Cruising didn’t die with cottaging. At any one time there are tens of thousands of guys on Gaydar or Grindr, most of whom are probably looking for a quick fuck. Yet there is an important distinction: cottaging often relies on immediacy and spontaneity, online cruising is more deliberate. When you log into your Gaydar or Grindr account, you immediately begin to image manage: you tick boxes about the sort of person you are, what you like, what you dislike, you literally chose the image you present to the world. In effect, you bring all the baggage of your everyday life with you to make sex self-conscious. There is something slightly sanitised and restricting about it.

We do not know what Jeff Ak ers was doing when he was murdered. But perhaps he felt the lure of cottaging, like so many others past and present. In my case that lure was a quest for that one defining, near-perfect sexual experience. I don’t see anything wrong with that. In a way it is rather quixotic.

ers was doing when he was murdered. But perhaps he felt the lure of cottaging, like so many others past and present. In my case that lure was a quest for that one defining, near-perfect sexual experience. I don’t see anything wrong with that. In a way it is rather quixotic.

So this is not an argument in favour of sex in public toilets. This is an argument in favour of sexuality. That is why cottaging still matters.

Graham Kirby is currently filming a documentary The Strange Decline of the English Cottage. You can follow him on Twitter @grakirby.

I think you miss the point of the article Jimmy. Rarely is anyone thinking academically when they’re looking or having sex. I imagine many people look back on cottaging and romanticise about it, I certainly do. Never did I feel oppressed, I felt excited, a byeproduct of its illegality. i guess the war wasn’t the best days of the oldies lives either